709-218-7927 The Landfall Garden House 60 Canon Bayley Road Bonavista, Newfoundland CANADA A0C 1B0 |

|---|

Why I Blame Mercator and The Brits for the Afghan War

The most recent phase of the “War in Afghanistan” (a.k.a. “The Afghan War” a.k.a. a whole lot of other titles including “ The Story of the Malakand Field Force ” by a (then) new author Winston Spencer Churchill) is coming to an end as I type this. The Taliban have re-taken control, and parts of the world believe that the world has come to an end. I remain optimistic, because for twenty years women have been able to walk unattended, drive cars, be educated in schools and universities, and a great many other things that some of us take for granted.

That means that residents in the age range 10-30 years have experienced and, we hope, come to love that type of life. And that means that a whole generation exists with a deep longing to return to that kind of life. Once you experience a sample of what is, by your standards, “a better life”, you want that type of life full-time. That is why I moved to Bonavista.

But the recent occupation (20 years) by allied forces was just the one that followed the occupation by Russian Forces that began while I was still working in France back in 1980. And that occupation/war was preceded by ...

Well, my first knowledge was gained by reading WSC’s book, published in 1898. I probably obtained my second-hand copy a hundred years after that.

What was Britain doing in Afghanistan in 1897 and the years before that? In simple terms, Britain was defending “The North-West Frontier” (think “Khyber Pass”) against the Russians (think Rudyard Kipling and “Kim” and the tale-end [sic] of “Stalky and Co.”)

Why was Britain defending The North-West Frontier” against the Russians? To the best of my limited knowledge, Russia wasn’t attacking the North-West Frontier, which the Brits saw as the gateway to India (think “Pakistan, India, Burma and points east”), but the Brits thought that Russia might attack.

Why did the British think Russia might attack? Because those in power (British politicians and army and naval officers) were educated at Oxford and Cambridge universities, and that meant that they were very good at Latin and Greek translations. At sciences, in particular geography and mathematics, not so good.

Britain, remember, controlled Pakistan, India, Burma and points east and a large number of oceanic islands that served at coaling stations (in those days, and continue their albatrossic nature to the current day; why else fight for a few thousand sheep and their acreage?). Britain was a maritime nation. Those who thought that Britain was the greatest maritime power in the world thought that Britain was the greatest power in the world, which is what won them the pole position in The Great War.

In 1560 Gerardus Mercator presented the maritime world with The Mercator projection . You know this map well, because it was the map on your classroom wall. Anything British was in pink (“ The sun never sets ... ”).

Why was Mercator’s projection important?

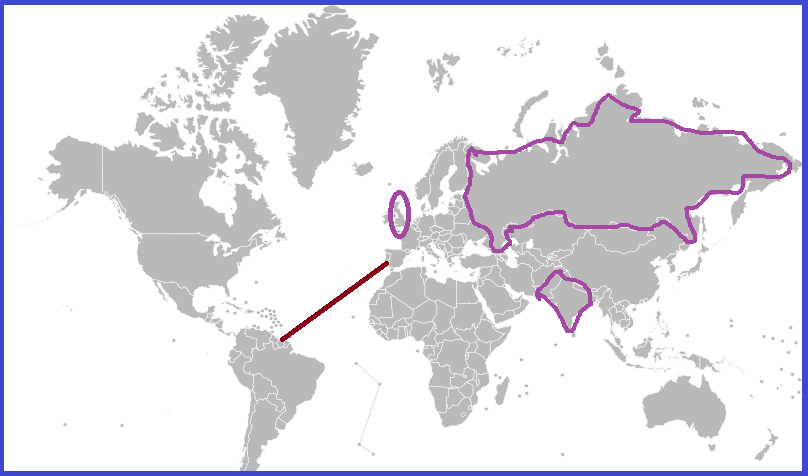

Mercator’s projection when used in a specific range of latitudes (the European theatres of sea-farers) allowed a navigator to read from the flat map the angle to head in order to get home. For example, if you are leaving French Guiana and want to head home to Portugal, the Mercator projection shows the straight-line route on the map as a heading of forty-five degrees. Aim your ship at a constant heading of 45º and you’ll be in Lisbon lickety-split. No need to worry about lat/long or chronometers.

Mercator’s influence on ocean navigators and by extension maritime nation’s naval powers - and at this time that meant Britain – is great because the ocean is featureless. On the 11-day trip across the Indian Ocean from Colombo to Fremantle, the view from ship looks the same every day. On land not so much. You want to travel from London to Moscow, cross The Channel (by tacit agreement there is no need to specify whose channel) and collect some chocolate in Brussels, perfume in Cologne, sausages in Frankfurt, then take this road to Berlin, ... and along the way you can check your route with other travelers, perhaps see the bright lights of the next city at nighttime. At sea not so much.

So read the angle off the map, relate this to the helmsman, and then read the latest John Grisham paperback until you are in Lisbon harbour. Easy-Peasy. If you were British you worshipped Mercator’s projection.

Now to a Latin or Greek scholar whose home was in Nether Wallop or Sheepy Magna, a glance at the regular maritime map is enough to see that Russia is about twenty times the size of India, and if India has a population of about 150 million, then presumably Russia must have about twenty times that (takes off shoes and socks to count), say three billion. What an army that would make!

Time to panic.

And look! Russia is ABOVE India; it has gravity on its side. Mathematics, Newtonian Physics, and Geography were not strong points in the classical education of the aristocracy.

Time to panic.

No matter that most of Russia is uninhabitable, there are practically no railways (for troop assembly), and no super-highways to speed tanks and guided missiles South to India, and no navy to speak of and Britain ruled the waves, and ...

Mathematics, Geography were not strong points in the classical education of the aristocracy. You didn’t need to work, you see; you just needed to govern, and that depended largely of who begat you.

Well, anyway, Mercator should have put a warning on his maps “Caution: Objects at the top are smaller than they appear”.

There is a summary under the heading “Background” at this Wikipedia page

I have enjoyed the 1988 movie The Beast ..

[later] Just one week after I wrote this, The Australian Broadcasting Commision ran a story that included this text:-

“That placed it from the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, when the British Raj fought the Emirate of Afghanistan to assure a buffer between the Russian empire and British interests in India and Persia. Lieutenant Colonel Huxley, the commanding officer of Mentoring Task Force 2, remarked what a blighted history the rifle represented. Seized or stolen from a British or Indian soldier, the rifle would have soon seen action in Afghan tribal conflicts. It was probably used against the British in their third invasion of Afghanistan, shortly after World War I and then against Soviet Union troops in 1929-30 and again in 1979.”

Told you so!

709-218-7927 CPRGreaves@gmail.com Bonavista, Saturday, December 20, 2025 10:02 AM Copyright © 1990-2025 Chris Greaves. All Rights Reserved. |

|---|

Friday, August 22, 2025

See also " Mercator map isn’t a crime against Africa "